MARK AND DAN’S EXCELLENT ADVENTURE, PART II

By Dan Woodhead

You may have read in the first Part, how my son Mark set up a Rock Shox tour with Western Spirit Cycling (WSC), of Moab, Utah, in October 1996.

(It was called the Rock Shox Tour because that’s the company Mark works for. They make shock-absorbing spring forks for mountain bikes. Mark was the only Rock Shox employee on the tour, as it turned out, The other tour members were me, his sister, his girl friend and assorted other friends.)

WSC took us on an awesome guided tour of some of the rough country south of Moab, Utah. They carried our gear in a 4WD GMC, cooked meals for us, guided us (on mountain bikes), gave tips on riding (although they allowed as how we were one of the faster and more expert groups they’d guided), and explained the flora, fauna and geology of the area. But they didn’t take us into the Abajo Mountains south of Moab to ride on single track (narrow paths, as opposed to double track, such as fire roads and jeep roads) at high elevations. An early snowstorm prevented that. In fact, WSC had two tour groups up there at the time. They were stranded for two days in the mountains because they couldn’t move the vans, and couldn’t ride the snowy, muddy trails. Luckily, they had plenty of food.

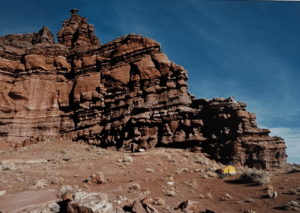

Mark talked me and three of his friends into going back this May (to see if we could get into the mountains. I flew into Salt Lake City, and then on to a small airport near Moab on May 14, 1998, picked up a rental car and drove out to the primitive campground at Sand Flats by the Slickrock Trail, on the outskirts of Moab. I found an unoccupied camp site in the sand backed up against the edge of the slick rock, set up my tent, and settled in to wait for Mark and his buddies. Primitive means no telephone, no electricity, and no running water. When it got too dark to read (around 9 pm), I crawled into my sleeping bag and went to sleep. It was cold that night especially in my old WWII-surplus sleeping bag, and I eventually ended up sleeping in my clothes in the sleeping bag, and was still uncomfortable. It warmed up gradually through the week, though, and the rest of the nights were okay

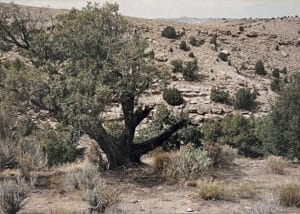

Mark and his friends were supposed to show up next day (the 15) between noon and 2 pm, in a borrowed 32-foot long Tioga RV. So I sat in my camp, at a picnic table that someone had dragged into the semi-shade of a pinyon tree, reading and watching the parking lot (there was no shade out there).

Mark and his friends arrived around 4 pm, after driving all night from Santa Cruz, CA. They’d gotten a late start. After introductions (I knew Mark’s old friend Wolf Bloss, and met two new ones, Geoff Smith, and Mark Karlstrand, from the mountain-biking club in Santa Cruz), we surveyed the remaining supply of camp sites close to the parking lot, and they decided to join me in my relatively large one. They rolled the RV into the site, leveled it as much as possible, chocked the wheels, and unloaded the bicycles.

Mark brought two bikes so I could ride one. The twin-turboprop aircraft that Alpine Airways operates from SLC to Moab has only 10 seats, and doesn’t have room in the baggage compartment for bikes, so I’d left my mountain bike at home. Mark decided to have me ride his fully suspended Santa Cruz a $2000+ bike with a Rock Shox fork and a pivoting rear triangle with a Rock Shox air-oil cartridge to provide springing and damping in the rear. It’s kind of like an off-road motorcycle without a motor. But it has 24 speeds, with real low gears. He chose to ride the hardtail bike he’d built up on a Schwinn Homegrown aluminum frame. It has a Rock Shox (what else!) front fork, and no rear suspension. But he’s fitted it with a prototype suspension seatpost, which smooths out the bumps a little bit.

Wolf and Mark K. were also riding fully-suspended Santa Cruzes, but Jeff, something of a retro-grouch (that’s someone who doesn’t believe in replacing a perfectly workable old part with the newest development), was riding an un-suspended Specialized, with friction shifting. Clipless pedals were his only concession to the latest technology. He substituted skill and strength for a plush ride and positive, error-free shifting.

We all headed out onto the Slickrock Trail right next to the parking lot.

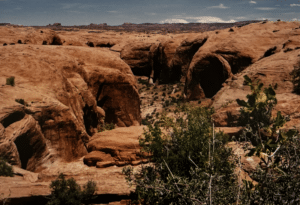

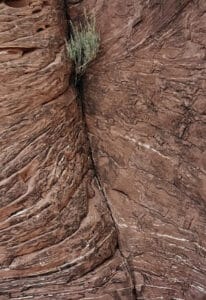

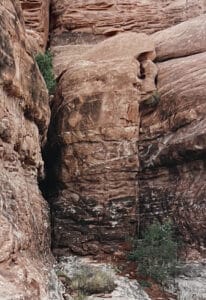

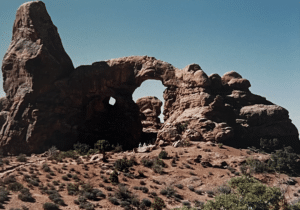

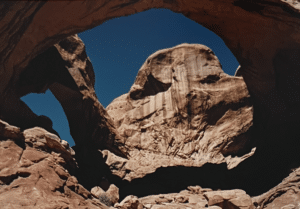

“Slick rock” is not really slick. It’s not even all that smooth, but it looks smooth from a distance. It was made by wind-blown red sand, which was then covered with other sedimentary deposits, turned into stone, and eventually uncovered again by erosion. Back in the 70’s, an off-road motorcyclist got the idea of laying out a trail on the dune-like rock, got or permission from the Bureau of Land Management, which owns the land, and painted dashes on the rock to show the best trail. There’s a 2-mile “practice loop, and a 12.7-mile main loop. When mountain bikers discovered it, word spread, and the Slickrock Trail is now world famous among mountain bikers. It, and the jeep roads and foot paths through the red rock deserts and aspen and fir-covered mountains in the area have made Moab a mountain-biking Mecca.

We decided to just do the practice loop that first late afternoon. On the first downhill, I got nervous when the trail pitched down sharply, and reacted automatically. I grabbed the brakes to slow down. What you’re supposed to do is slide back on the seat, if necessary putting your belly on the seat and hanging your rear end out over the rear wheel, and drop your head down toward the handlebars, to lower your center of gravity and the roll center of the bike. And feather the brakes! I grabbed them tightly in my momentary panic. Mark’s brakes are much stronger than mine a newer design, including a cable-actuated hydraulic disk brake on the front. Before I knew what had happened, I was doing what is technically known as an “endo” for “end over end,” I suppose. By the time all motion stopped, I’d bruised my rib cage on the right, collected a number of spectacular areas of “road rash” wherever my skin contacted the slick rock, and lost a lot of dignity, and whatever claim to technical trail-riding skills I might have had.

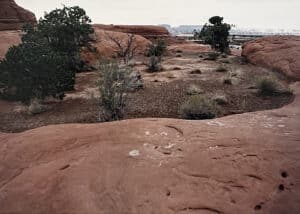

We went around the practice loop once. It’s really like a giant free-form roller coaster where you’re in charge sort of. It’s all open, and you can ride wherever you want to, but it’s best to follow the painted dashes. They keep you from riding over steep drop offs, down unrideably steep slopes with sharp transitions at the bottom, or through basins in the rock that have cryptobiotic soil in them (it’s an ecological faux pas to ride or walk on cryptobiotic soil the blue-green algae in the crust holds the sand from blowing around, and recovers slowly after such an assault, so the evidence of your indiscretion lasts for years).

The slick rock has steep up-slopes and down-slopes, bumps, places where it drops down off the rock into deep sand (where you have to sit back and spin to keep from bogging down and doing an endo), and even mild, relatively flat places where you can catch your breath. The rest of the group thought it was so much fun, they decided to do it again, since there was some more daylight left. I elected to wait for them, nurse my bruised ribs, and watch other riders struggling up the hill to the starting point.

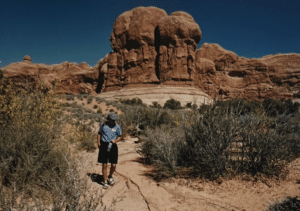

Next morning, after breakfast, we decided to ride the Porcupine Rim Trail. We tuned the bikes and lubed the chains, stuffed energy bars into our pockets, and filled our water bottles and Camelbacks (a hydration system that fits on your back, and has a vinyl bladder that holds a half gallon or more, with a tube that hangs close to your mouth so you can drink with your hands free to manage the task of bike handling). We rode out of camp and onto the road from town. We turned right and headed uphill sometimes sharply uphill. The road turned to dirt. Vehicle after vehicle passed us, loaded with the bikes of less-determined riders, and stirred up dust as they went by. After several miles, we came to the staging area for the Porcupine Rim Trail. We turned in to the left, and headed up a rocky, sandy, fairly technical (difficult, requiring technical bike-handling skills) single track.

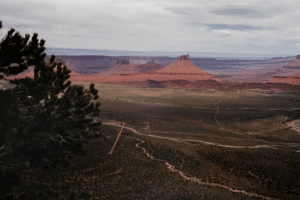

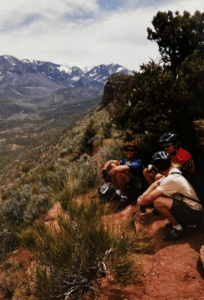

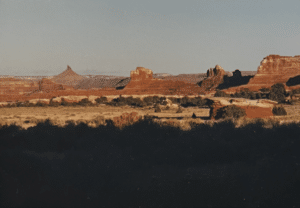

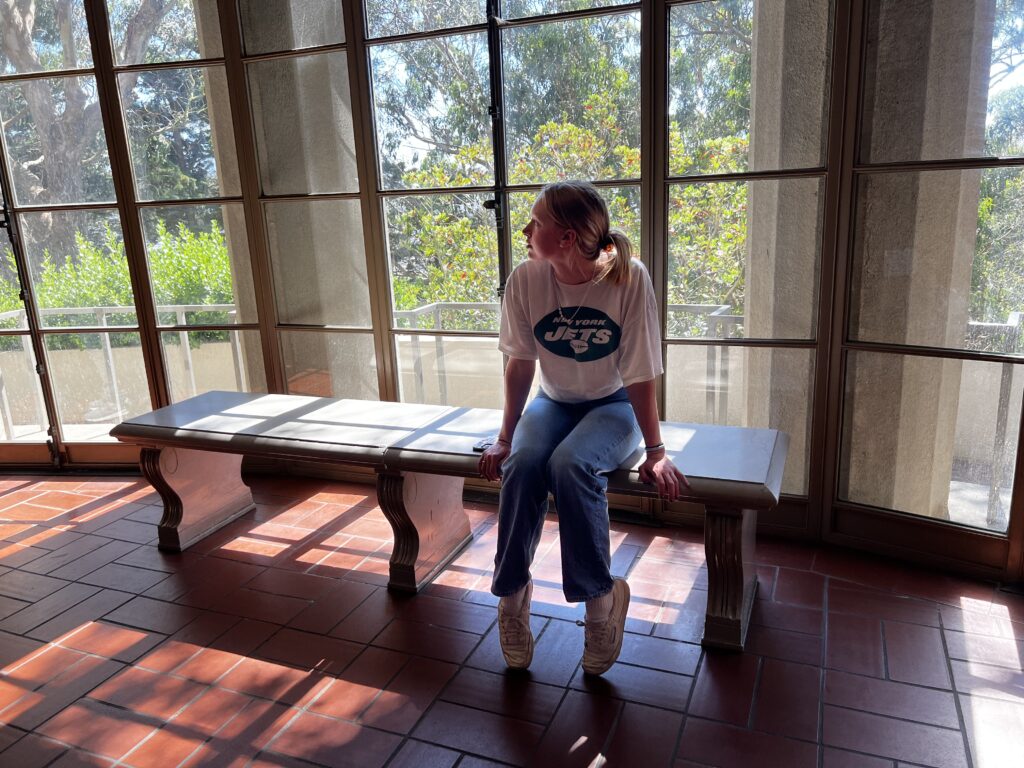

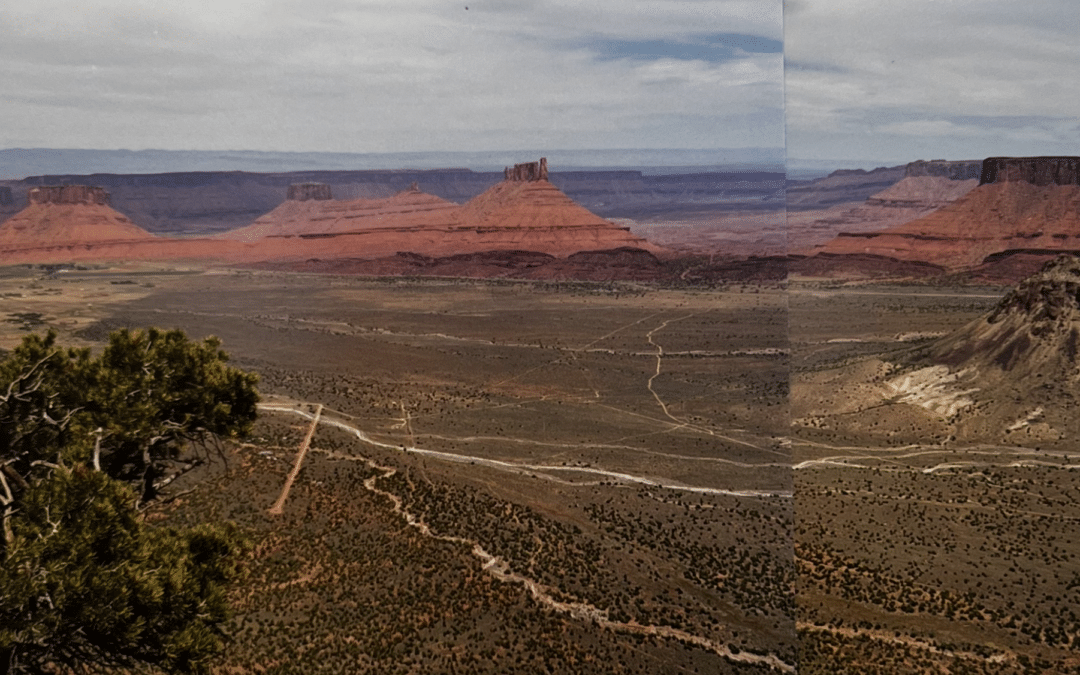

There were quite a few riders on the trail- especially in view of the notation in the guide book that it was “notorious.” A number of them were women, and many of the riders seemed less strong and less skilled than I was and I’d considered my own state of readiness to be the ragged minimum for this trail. There was even a young kid on an inexpensive 10-speed mountain bike, gamely riding along with his father. After a couple of miles of difficult up-hill single track, we came to a wide area of bare slick rock, But covered with laid-down bikes, with riders standing around looking out over a cliff that dropped down to a wide valley far below, with mesas off in the middle distance, and haze-blue mountains on the horizon. We rested there, drank some water, ate some food, looked out at the view and took pictures. After a while, we headed out along the ridge. It was level (sort of) for a while, and then started dropping down, and curving around toward the Colorado River.

One section, which I decided to walk down, was quite technical. Mark W. took his Schwinn Homegrown down the right side, which consisted of an irregular set of red sandstone steps, each about 8 to 12 inches high. He got out of synch with the bumps, lost control, and did a mild endo. No major damage to bike or rider but, in the crash, the handlebar swung past the top tube of the bike, and snapped off his front brake lever. “I knew I shouldn’t have bought plastic levers!” Mark said. But he splinted the lever back together again with a piece of wood and some duct tape. It worked for the rest of the day.

Going down the next section, I found a steep patch of rocks and sand that looked tricky, and again applied the brakes too enthusiastically. Did another endo, but lost less skin in the sand and smooth rocks. Shortly after that, I took a bad line and ended up in a pinyon tree with my brakes locked up, and the bike almost stopped. The pinyon tree was scratchy! After that, I was more careful. (The major secret seems to not be afraid. If you let the terrain intimidate you, you’re more likely to crash. Also, you need to keep your attention out ahead of where you are, so you can plan a little and avoid surprises. The bike will find its way through the stuff close in without too much supervision from you. But that takes a while to get used to.)

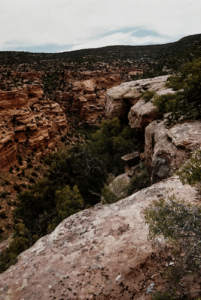

It soon became pretty important to be careful. When the Colorado came in view off to our right, the trail narrowed to less than a foot wide for the most part, and sections of the trail ran along a steep high cliff that dropped away on the right. I didn’t notice what Mark and his friends did, but I walked parts of that. A mistake would have meant falling a long way. You might not fall all the way down to the Colorado, but it looked as though you’d get pretty close, even before the first bounce.

Eventually, we came down to the river and the road that runs along it. But not before we’d carried our bikes over rough sections that couldn’t be ridden, even if you were willing to take chances. By the time we set out along the highway beside the river, I found I’d drained my entire 72-oz. Camelback, and was facing a dry run back to the campground in the hot sun. Fortunately, we found a spring near Moab, where water gushes out of a pipe sticking out of the cliff. We all swung over and filled our bottles and hydration systems before riding on along the highway to Moab.

Mark, Mark and Geoff are iron men. They were back in camp while Wolf and I were still struggling up the hill from Moab to the Sand Flats campground. But everyone agreed that the Porcupine Rim Trail was a formidable ride. It was 25 miles the way we did it, without a shuttle to the trail head and back from the end by the Colorado. That’s a moderately long ride on mountain bikes. But it was the roughness of the terrain that took its toll. Several of us had blisters on our hands from hanging onto the grips through the rough sections.

We were all determined to ride the next day. That was what we were there for, after all, but we agreed we were ready for a recovery day a mild ride over flatter terrain, with less technical riding, that would let us spin easily and let our muscles recover.

The guys set the cooler filled with beer and soft drinks, and a bowl of salsa and a large bag of taco chips (for carbohydrate loading, to replace the glycogen we used up during the day) out in front of the RV, and Mark W. set up his work stand so we could clean and lube the bikes, and repair any damage done during the day. Mark duct taped a small piece of metal tent stake we found on the ground in the camp side onto his brake lever, for a more permanent field repair. It lasted the rest of the trip. And he took Mark K.’s rear shock off to take it into town. Mark K.’s a bit of a rough rider, and he blew out the shock absorber’s seal on the ride that day. Since the unit is both springing and damping for the rear suspension, the bike couldn’t be ridden without it. We jumped into the car and drove into Moab, bought some food, and dropped off the rear shock at one of the local bike shops for rebuilding. That night, we barbecued chicken over mesquite charcoal we’d bought in town, and finally went to bed around midnight..

Next day, after a big breakfast of bacon and eggs and coffee (Geoff likes good coffee, and brought coffee, an insulated carafe, and filters with him), we drove into town in the rental car, stopped by the bike shop and picked up Mark K.’s shock absorber (it cost about $40 to rebuild it thank God for plastic!). Mark W. reinstalled it back at the campsite. Around midday, we fired up the RV, loaded the bikes in, and drove North from Moab to a gravel parking area in the desert. This was the trail head for the Monitor and Merrimac Trail, a flat 15 mile-long loop that was mostly dirt road.

At first, part of the road was loose sand that we couldn’t ride through. We pushed the bikes through those sections, and got back on where it got hard again. The trail then led over a wide section of ledge, marked with paint blazes. We found broken pieces of agate there that Indians had chipped to make stone tools at some time in the past. The trail over the ledge ran between spectacular red sandstone mesas. (One presumably looked like the Civil War ironclad Merrimac, and another like the Monitor.) The ledge ended with a long downhill ride to an area of cottonwoods bumpy and undulating, but not technical. At one point, Mark W. swung back to warn Wolf and me that we had to follow the blazes exactly, because there was a three-foot drop off just to one side of the indicated trail.

The ride was mild—just what we needed for a recovery day. Nevertheless, Mark K. found a sharp ridge in a shallow creek crossing, tried to bunny hop his front wheel over it, misjudged it, and hit the ledge. Major damage to his rim and tire! We stopped and Mark W. loosened the spokes at the dented part, we stuck a piece of dead root through there, stood on the root and pulled up on the wheel to sort of smooth out the flattened section of rim. Then Mark smoothed out a dented-in place in the rim, trued the wheel as best he could, cautiously re-inflated the damaged tire and we rode on.

The trail ran on a dirt road through cottonwoods along a stream for a while. We stopped at one point and walked a marked trail with dinosaur bones and petrified wood, leaving the bikes unlocked, leaning against the signpost at the beginning of the foot trail. That made us a little nervous, but it’s pretty safe in that area. Dinosaur bones look pretty much like rocks. We wouldn’t have known what they were if they didn’t have signs pointing them out and describing them.

Back on the dirt road, we rode on back to the RV, loaded the bikes in, and headed back to camp, and a spaghetti and meatball dinner. And, of course, salsa and tortilla chips, and beer and soft drinks. On the way through Moab, we stopped at the bike shop, and Mark K. bought a new tire (a gnarly one that cost $40) to replace the one he’d damaged in the creek crossing. Mark had a used front wheel he’d brought along, which he sold to Mark K. that evening for $27 after some hard, but good-natured bargaining. Mountain biking in Utah can be expensive!

Next day was the full Slickrock Trail. It’s only 12.7 miles long, but the sign in the parking lot warns you to allow 4 to 5 hours and to take plenty of water. We did it without incident or rather, without accident. I walked up some parts, and down some parts. It was just too steep to take a chance on. Sometimes, I’d try to make it up a section, knowing that I could yank my right foot out of the toe clip, swing the front wheel out to the left, and stop the bike in a stable position with one foot down, and holding it there with the brakes until I could climb off and push it up a slope I was too tired to manage, or that was too steep for me to both keep the front wheel on the ground, and give the rear wheel enough traction to keep the bike going up. Wolf walked a few places, too, but he seemed to have better climbing skills than I did. Mark, Mark and Geoff may have even walked a few spots, but I didn’t notice.

At one point where we stopped to rest, Mark W. and Mark K. found a bowl up on the left that they could ride up into. As long as they kept going and made a loop at the top, they could ride it without falling. A photo opportunity! Later on, on a spur out to a view of the Colorado, we found a big pot hole, about 18 feet wide, and at least that deep, with sides that curved downward until they were vertical near the bottom. We speculated as to whether one could ride down into it and, by keeping enough momentum, use centrifugal force to keep from crashing to the sandy bottom of the pot hole. Trouble is, there was no way to get back out, and it looked pretty doubtful as to whether anyone could get down the vertical sides safely. Mark and Mark K. contented themselves with riding into the top of the sloping sides of the pot hole just a little bit, and riding on out the other side. Made me nervous!

This day was Geoff’s turn for equipment problems. Midway through the ride out on the slick rock, the escapement mechanism on his recently installed rear hub stopped working. That meant he couldn’t stop pedaling. He essentially had a fixed gear, like track bikes, or road bikes around the turn of the century. But because he had the derailleur, he couldn’t use the pedals for braking the way you can with a track bike, because the chain would wind up into the derailleur, and jam up. So Geoff shifted into a higher gear, used his brakes more on down-slopes, and pedaled downhill. It worked, because of his strength and skill. At the end of day, we drove into Moab to the bike store, where they inspected the damaged hub, and sold Geoff a new wheel for about $120. We were getting to be real good friends with the people in the bike shop by now.

Next day was Tuesday. Mark wanted to try the single track up in the Abajos. We stopped by Western Spirit, and talked to Ashley Korenblat, who owns WSC now. They didn’t have good intelligence on the condition of the trails, and were too busy scheduling trips to have time to check it out. The Forest Service down in Monticello said the roads were probably on snowed in up at the upper levels, but they hadn’t been up there for a while. Ashley asked us to report back to her if we tried it, since they had a tour scheduled there in early June, and were getting worried about it.

We headed down to Monticello in the RV and the rental car, swung off and left the car at a rough campsite by a creek near Newspaper Rock, and then drove the RV back up through Monticello, turned up the mountain road, and parked in a turnoff in an aspen forest at around the 8200-foot level. It was a lot cooler up there than it had been down in the desert, and seemed more like spring. There was a small stream flowing down through the aspens, and the ground was wet. We got the bikes out, put on tights, and took jackets and rain gear with us. We headed up the dirt road, and after about a quarter of a mile, found the road blocked with snow.

The snow was about a foot or so deep, corn snow, and melting, but it was packed down on the road, and we found that, for the most part, we could walk on it and push the bikes. Every once in a while, though, your foot would break through, and you’d go in up to your knee. Our cycling shoes and socks got soaked after a while. Then it began to rain. Just a little, but it wasn’t a good sign. It had been 2 pm by the time we left the RV, and it was getting late. We were hoping that when we got over the top of the ridge, we’d find less snow in the road on the south side of the mountain, so we could ride and make better time.

Near the top, Wolf, Mark K. and I sat down to rest, wring out our socks and eat some energy bars, while Mark W. and Geoff scouted ahead to see how things looked. It had been sleeting, but the sun was out intermittently again, and it was kind of pleasant. But it was now 4 pm, and we were getting worried. We decided among ourselves that 4:30 was the turn-around time, when we’d either decide it was a reasonable gamble to go on, or time to turn back to the RV. About that time we heard a shout from the ridge, and Mark and Geoff were waving to us to come on up. We pushed our bikes straight up the slope, which seemed to be a ski slope (though there was no sign of a ski lift), rather than following the switchbacks of the road.

At the top of the ridge, Mark and Geoff were drying their feet while they waited for us to come up. They’d scouted down the road on the south slope a little way, and it looked pretty good, they said. So we decided to go on. It would be pretty much all downhill from here. It was. And the road was free of snow in a lot of places. Sometimes we’d have a foot or so of wet gravel between the downhill slope of the mountain and the snow that filled the rest of the road. Sometimes the road was entirely clear. Every so often, we had to stop and climb over a snowdrift, but it was getting better all the time, with less snow.

Eventually, we turned off the dirt road onto single track that cut across a steep slope through a grove of aspen saplings. The trail led into a grove of large fir trees. We were generally following a stream that I think was Indian Creek. It was down below us on the left. Coming down the trail at one point we could see a grove of aspen trees on the slope across the creek, lit up by the late afternoon sun. It was beautiful- -what Ansel Adams would have photographed if he’d done color.

A little further on this single track I had my only accident of the day, and the last of the trip. I rode up to Mark, where the group had stopped for a break, dodged a rock or something, and stopped. Mark said, “Nice save, Dad.” And at that point I toppled slowly over downhill and landed on a rotten 6-inch thick log on the slope below the trail. It hit me low on the left side and knocked the wind out of me. I could feel that it pushed into my rib cage more than was natural, and figured I’d broken some ribs. As I lay there groaning, Mark became concerned, and I guess he was wondering what he’d say to Carolyn after they had to medevac me out by helicopter. But we got the bike up, I climbed back up on the trail, and we assessed the damage. No ribs seemed to be sticking out or pushed in, although the area was pretty sore. We rested there for a bit, and I ate an energy bar, drank d some water, and decided I felt better than expected.

We continued on down the trail, but I only rode when the trail looked pretty easy to handle. I wasn’t at all sure that no ribs were broken, and that the next fall wouldn’t puncture a lung. The trail took us down by the creek, and led through a flat area that I felt confident in riding. Presently, we came to a ford. Geoff took off all his clothes and waded across with his bike he wasn’t sure how deep it was going to be. Turned out it was only 12 to 18 inches deep, though the water, which was snow melt, was cold, and pulled at our legs when we lifted them to take a step. The footing was pretty good, though. The rest of us just took off our shoes and socks, and pulled up our cycling tights to cross. Mark carried my bike across and I was happy to let him, since I thought that carrying it would hurt a lot.

In a few hundred yards, we saw a couple of men camped in a meadow. Across the creek. This time, I just pulled up my tights and left my shoes and socks on. The men pointed out where the trail went up the hill-_back on the other side of the creek where we’d just come from. They said it was just a short climb to where they’d left their jeep on a dirt road. It was all easy downhill from there. We warmed ourselves by their fire for awhile, thanked them, and waded back across the creek.

We climbed the hill, pushing over a few final snowdrifts on the trail through the aspen woods, and finally came out into an open grove of big aspen trees with grass growing in between, and a path winding through it. We got back on the bikes and rode up through the aspens on a gentle up-grade. It was beautiful. The sun was almost down, though, and we had a long way to go.

Soon we came to the dirt road. We headed down in the dusk—a long sweeping coast downhill on a pretty good dirt road. I found it was best to let the suspension handle the waterbars we kept crossing, rather than trying to bunny hop them. The pain in my ribs was less from the jarring than from yanking the front wheel up. Eventually, we came to a trail that led off the dirt road, along Indian Creek. We could have followed the road, but it would have been much longer. The trail would only be about 11 miles. It was really getting dark. At first, we followed the trail by using the light from the sky and letting our eyes become accustomed to the darkness. And for a while, we could ride along the single track. Eventually, it was too dark to ride, and we walked the bikes. Where the woods got thicker, we couldn’t even see the trail and had to feel our way along. Mark K. was on point.

Soon it was too dark to even walk with any confidence, even in open areas. Fortunately, Geoff had a penlight. He walked near the back of our procession, holding the light near his helmet, so it sort of illuminated the trail, and Mark K. could see where it went. This was critical at times. The trail sometimes ran right along the bank of Indian Creek, and it would have been possible to step off and slide 30 feet down a rough bank in the dark and end up in the creek. And every so often, the trail dipped down into a dry wash, generally with rocks sticking up out of the sand.

Eventually, Geoff’s batteries gave out. But Mark W. had a helmet light designed to flash red to the rear. It had two A cells in it, and they swapped batteries. We went on, and eventually came out in an open field filled with sagebrush and juniper. The trail was really narrow, and I kept dinging my shins on my sharp pedals. The rest of the group was doing the same, but their clipless pedals were less hostile, so they fared better. The sagebrush gave off a strong aromatic smell when we brushed it. It smelled like WD-40 to me. We went through a couple of cattle gates (three strands of barbed wire tied to a movable post that was tied to a fixed post by two wire loops), crossed Indian creek one final time, and came out on a dirt road.

We could see a cliff looming in the darkness up on our right side, and I was sure we were near Newspaper Rock, where we’d left the car. Wishful thinking! We walked on another hour on that dirt road, startled a herd of cows and sent them running off through the dark with one cow’s cowbell clanging hollowly, and finally came out on the road near the campsite. It looked good! It was a 25-mile ride, and over half of it had been done walking and pushing our bikes. We were wet and tired. But everyone agreed it had been a wonderful adventure, and a nice change from riding in the desert.

We hauled the precious cooler of beers, the quart jug of salsa, bags of tortilla chips, and the camp chairs out of the trunk of the car, and lit a fire. Our planning hadn’t been perfect, but this part was carefully planned. Geoff, Wolf and Mark K. sat down to relax and guard the bikes, and Mark W. and I each took a Coke, got in the car and headed back to get the RV. It was 1:30 am.

Along the way we saw a lot of kangaroo rats jumping along the road through the desert as we drove back toward Rt. 191, the main north-south road in the area. May have run over a few. As we drove up the mountain road from Monticello, we had to keep slowing for deer, who’d come up to the road, slow down and mill about as we approached them. We also saw a big porcupine ambling off the road to the right.

Eventually, we got to the RV, swung the car around, got out the jumper cables, and started the RV. (It needed some maintenance, and one of the things it needed was a new main battery. Sometimes the accessory battery, which runs the RV’s interior lights and accessories, and can be switched over to start the vehicle, ran down, too. I was glad I’d decided to keep the rental car for the whole week; it was invaluable in lots of ways.) We drove back to Monticello, fueled the RV, and bought some fuses. The running lights and tail lights on the RV had gone out, though the headlights, brake lights and turn signals still worked. The fuse blew when Mark installed it. So we gave up and headed back to Newspaper Rock, arriving there at 3 am. We spent the night there; no one wanted to drive back to Moab that night. Geoff gave me a 600 milligram ibuprofen tablet for the pain in my ribs. I took it, and slept comfortably until I smelled Geoff’s coffee brewing next morning.

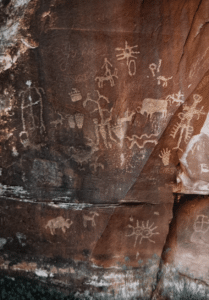

Next morning, we had a big breakfast—a pound of bacon, 18 eggs, onions and mushrooms, all fried up together, and a pound of frozen pan-fried potatoes that Wolf had bought earlier in the trip. We walked down to b to Newspaper Rock, a cliff with Anasazi petroglyphs on it, took photos of the area, and then unlocked the bikes from the tree next to RV, loaded them in, and drove back up to Moab.

There’d been some talk of riding the Slickrock Trail again on Wednesday before heading the RV back to Santa Cruz. I resolved to give that a pass. But by the time we got back to the campsite later in the morning, no one was very interested in riding that day. The guys packed up the RV, we said good by and they headed back into Moab to a trailer camp to dump the RV’s holding tanks, and to jury rig some rear lights to run off one of the interior light fixtures. (Wolf had bought an electric tester and tried to trouble shoot the short that kept blowing fuses, but hadn’t found it.) I drove in later to do some shopping (a little food, and Tony Hillerman’s detective novel A Thief of Time, about pilfering Anasazi burial sites in the four corners area where we were, and a map of the area and Edward Abbey’s book Desert Solitude, about his time as a seasonal park ranger at the Arches National Monument just up the road from Moab), and then went back to the camp site and packed up to be ready for my 7 am flight next morning.

I learned later that Mark and his friends stopped at WSC on the way down the hill from the campground to tell Ashley the trip through the Abajos had been AWESOME—but not to take any of her tours through there for a while. On the drive back to Santa Cruz, the main battery in the RV objected to having the alternator push current through it, and it fumed and spit liquid out. Mark said it smelled as if the battery was farting all the way to California. Whenever they stopped, they were careful not to go near the front of the RV till the battery had had time to cool down.

I thought of packing up the tent that evening and sleeping in the open, so that breaking camp in the morning would be simpler. Luckily, I decided not to. It rained all night, heavily at times. I could hear water running down off the slick rock and gurgling along the low places in the sand in streams. In the morning, the dirt road out of the camp site was flooded. I rolled up my wet tent and packed it in my duffel bag, folded up the wet, sandy ground cloth and left it for the next camper that came along (it was too heavy and grungy with the wet sand for me to want to stuff it into my bag), jumped in the car, drove through the flooded section and headed off through Moab to the little airfield north of town.

The 10-seater turboprop aircraft had only one pilot that morning, and only two passengers. It wiggled disconcertingly as we flew up to Salt Lake City. But otherwise the flight back to Dulles was uneventful.